Rocky Mountain National Park, CO Weather Cams

Alpine Visitors Center

Continental Divide

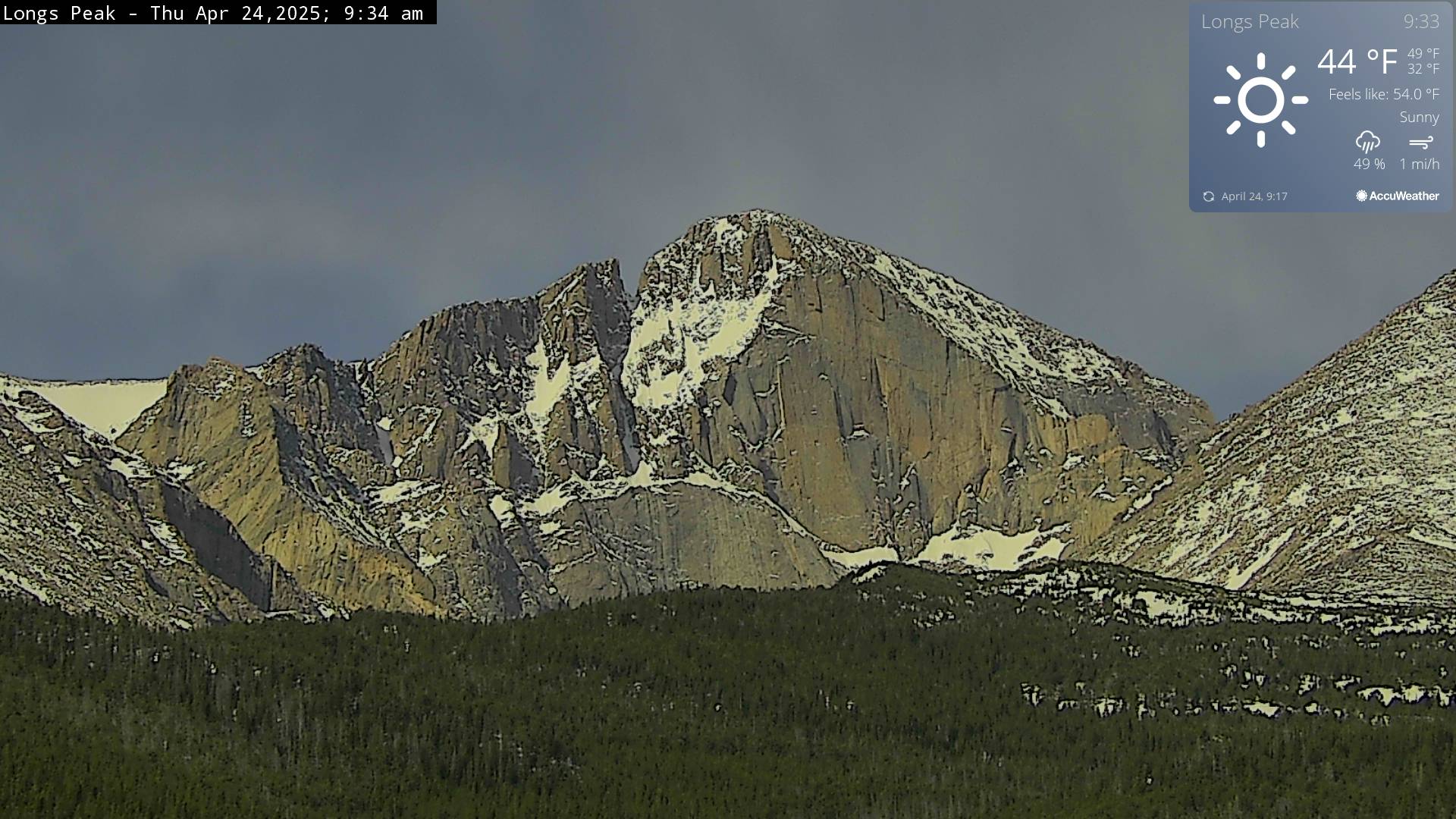

Longs Peak

Kawuneeche Valley

Fall River Road Entrance

Beaver Meadows Entrance

Rocky Mountain National Park CASTNET, Colorado – tower top (south of Estes Park, near Alpine Brook)

Crowned by the Continental Divide: A History of Rocky Mountain National Park and Its Surroundings

Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado Weather Cams. Nestled along the northern Front Range of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) preserves one of North America’s most iconic and ecologically diverse alpine landscapes. Its story stretches far beyond its 1915 designation as a national park—woven from deep geological epochs, Indigenous legacies, gold rush ambitions, and evolving environmental stewardship.

Ancient Origins: Geology and Early Peoples

Long before there was a Colorado, before humanity itself, the area now known as RMNP was forged by deep-time processes. The park’s granite backbone—the Precambrian rocks of the Front Range—formed over 1.7 billion years ago. Later, tectonic uplift during the Laramide Orogeny (approximately 70–40 million years ago) gave rise to the towering summits, including Longs Peak, which looms at 14,259 feet today.

Evidence of human occupation dates back more than 11,000 years, beginning with Paleo-Indian peoples who crossed ice-age landscapes in pursuit of game. Over millennia, Arapaho, Ute, and other Native peoples established deep connections to the mountains, using trails, seasonal hunting grounds, and sacred spaces across what is now the park.

The Ute people especially left a linguistic and spiritual imprint. The name “Estes”—for the valley just east of the park—was adopted by settlers but reflects their earlier presence. Arapaho hunters and scouts also traversed the high passes and called Longs Peak “Neníisótoyóóʼ”—“The Tip of the Mountain.”

Settler Incursions and Alpine Allure

In the mid-19th century, the region’s remote peaks became less remote as European American settlers entered the Estes Valley. Fur trappers came first in the early 1800s, followed by waves of fortune seekers spurred on by the 1859 Colorado Gold Rush. Though no major deposits were discovered in the park, mining activity proliferated around nearby towns like Allenspark, Ward, and the burgeoning settlement of Estes Park.

By the late 1800s, as the frontier mythos evolved, the Rockies became romanticized rather than exploited. Naturalists, artists, and affluent tourists flocked to Estes Park, drawn by clean air, sweeping vistas, and the promise of alpine rejuvenation. F.O. Stanley—co-inventor of the Stanley Steamer automobile—was so enchanted he built the grand Stanley Hotel in 1909. It not only drew elite guests but also helped catalyze the preservation movement by showcasing the area’s grandeur.

Establishment of the Park

The campaign to protect the region coalesced around Enos Mills, a self-taught naturalist and writer who tirelessly lobbied Congress to preserve the mountain wilderness. He emphasized its unique biodiversity, rugged beauty, and ecological significance as a “National Playground.” Thanks in part to Mills’ advocacy and a growing conservation ethic nationwide, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Rocky Mountain National Park Act into law on January 26, 1915.

The park’s boundaries initially encompassed 358 square miles, though they’ve since expanded modestly. It was among the first national parks created following the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 and remains a treasured symbol of that early conservation movement.

Ecological Richness and Changing Priorities

One of RMNP’s defining features is its dramatic range of ecosystems across elevation bands—from montane meadows and aspen groves to subalpine forests of fir and spruce, up to fragile tundra atop Trail Ridge Road (the highest paved road in any U.S. national park). The Continental Divide splits the park almost evenly, creating distinct eastern and western climates and habitats.

Wildlife such as elk, bighorn sheep, black bears, and more than 280 bird species thrive here. But ecological balance hasn’t always been a priority. Early park management emphasized tourism, constructing roads and visitor services often at the expense of wilderness. Trail Ridge Road, opened in 1932, was both an engineering marvel and a symbol of access over preservation.

In recent decades, however, the park’s mission has shifted toward ecosystem health. Reintroduction of fire regimes, protection of riparian areas, and active monitoring of climate impacts reflect this evolution. The pine beetle epidemic and changing snowfall patterns highlight the urgency: even this protected highland isn’t immune to global change.

Cultural and Scientific Significance

RMNP isn’t only a refuge for wildlife and wanderers—it’s also a living laboratory. Researchers monitor everything from glacial retreat to amphibian migrations. In 1976, UNESCO designated the park as part of the Front Range Biosphere Reserve, underscoring its global ecological importance.

Culturally, it has retained deep resonance. For

The Park Today and Tomorrow

Rocky Mountain National Park now receives more than 4.5 million visitors annually, making it one of the most visited national parks in the country. This popularity, while a testament to its allure, brings challenges—overcrowding, trail erosion, and wildlife disruption among them.

The park has responded with timed-entry permits, educational outreach, and increased collaboration with local communities. Estes Park, Grand Lake, and the surrounding region have embraced sustainable tourism and interpretive heritage, offering visitors both access and insight.

Yet the future remains uncertain. As climate change accelerates, treeline shifts, wildfire risk increases, and alpine habitats become more precarious. But Rocky Mountain National Park, shaped by glacial ice, Indigenous footsteps, and enduring wonder, stands as a testament to both natural resilience and human dedication.

Whether watched from the windy summit of Longs Peak or wandered quietly among aspens on an autumn morning, RMNP endures as a high country sanctuary—where the land remembers, and invites us to do the same.

many Coloradans and visitors, the park remains a rite of passage, a wedding venue, a spiritual touchstone. Trails like Bear Lake, Flattop Mountain, and Chasm Lake offer timeless communion with nature. The mountain light, sudden storms, and open vistas challenge and inspire generation after generation.

For more information, visit Rocky Mountain National Park’s official website.